Investments in the luxury goods industry in Indonesia have been fairly limited primarily due to the lack of luxury retail spaces in the country. Foreign players are dominating the industry landscape. The only notable domestic player is Trans Fashion, which is Indonesia’s leading premium fashion retailer owned by billionaire Chairul Tanjung’s CT Corpora. The opening of new retail stores for notable luxury brands, including Vertu, Hermes, and Louis Vuitton, is contingent upon the establishment of luxury shopping malls – a key distribution channel for these premium brands. With Jakarta currently experiencing a slowdown of shopping mall development as a result of moratorium imposed by previous administrations, luxury goods companies have started to open up spaces in other prominent cities including Bali, Medan, and Surabaya.

Indonesian luxury goods consumers

Driven by rising affluent population

Indonesia’s affluent population is characterized with a drive to try new products and are more value conscious. This indicates greater willingness to pay premium for better quality products and services and thus, less sensitive to price. A more unique character of the affluent population is that they are more value conscious. This indicates greater willingness to pay a premium for better quality products and services and thus, less sensitive to price.

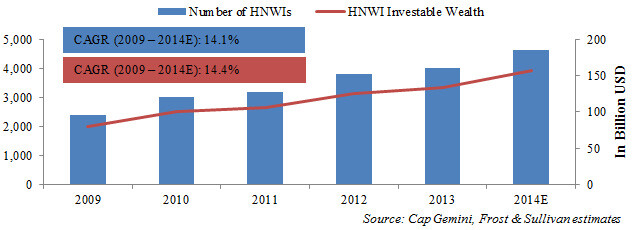

Frost & Sullivan estimates that population of high-net-worth individuals (HNWI)1 has grown at a CAGR of 14.1% between 2009 and 2014. In 2014, the number of HNWI reached 4,642 people. Interestingly, it is estimated that the total amount of wealth accumulated by HNWI increased more than the growth of HNWI population. Total investible wealth increased at a CAGR of 14.4%, reaching an estimated US$ 157 billion in 2014.

Figure 1: Number of HNWI and Total HNWI Investable Wealth (2009 – 2014E)

Frost & Sullivan believes that the affluent population will continue to drive the luxury goods market in Indonesia. One of the main reasons is due to the price insensitive character embedded in luxury goods market consumer base. This unique character allows the market to continue growing in the future despite any price distorting events, such as currency depreciation or sudden rise in import tariff for luxury goods.

Big spenders in neighbouring countries

The lack of luxury retail space in Indonesia renders consumers to travel abroad, most prominently to Singapore and Hong Kong, to make purchases of luxury items. Further, Indonesian consumers refrain from buying luxury products domestically due to more expensive price, as a result of then – high tax on luxury items, and not-up-to date product models. The fact that Indonesians are big spenders in other countries indicates the potential to further develop domestic luxury goods market

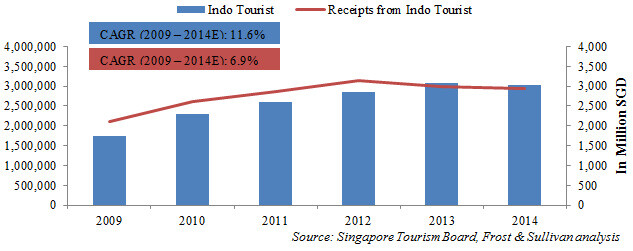

According to Singapore Tourism Board (STB), Indonesia consistently ranks at the top of international visitor arrivals to Singapore. Number of Indonesian tourists reached 3.0 million in 2014, increasing at a CAGR of 11.6% between 2009 and 2014. In 2014, tourism receipts received from Indonesian tourists reached S$ 2.95 billion, the highest compared to other countries, such as China, India, and Australia. STB noted that in 2013, around 56% of shopping items purchased was allocated to fashion and accessories products, in terms of the amount spent.

Figure 2: Number of Indonesian Tourists in Singapore and Tourism Receipts from Indonesian Tourists (2009 – 2014E)

Overview of the new luxury goods tax policy

In an attempt to jump start a sluggish economy, the government of Indonesia (GOI) issued a new tax policy that will exempt most goods from a luxury tax. The policy is promulgated under Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 106 / PMK 010, Year 2015 and will come into on 9 July 2015.The regulation, only the following goods are still burdened by luxury tax: luxury property compounds, hot air balloons, guns and bullets, helicopters, luxury ferry, and yacht. Previously, under Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 130 / PMK 011, Year 2013, the GOI imposed up to 75% luxury tax rate to various products ranging from electronics to branded fashion products to musical instruments.

The GOI argued that some of the products previously categorized as luxury products can no longer be considered as luxury items due to technology advancement and changes in product status. Technology advancement made some products, such as refrigerator, stove, and television, not attached to tertiary status anymore, due to declining price and thus, widespread usage. But, the main rationale behind implementing this policy lies on Indonesia’s worsening economic performance. The GOI expects that the policy will help the economy in terms of driving household consumption forward.

Implication to Indonesian economy

Luxury goods tax and domestic household consumption

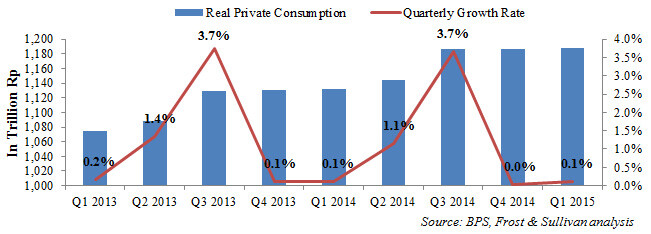

One of the key rationales behind this policy is that it will drive household consumption, amid deterioration in Indonesia’s economic performance. According to Indonesia Statistics Agency (BPS), the economy registered a 4.7% year-on-year growth rate in the first quarter of 2015, lower than the GOI target of 5.0%. On top of some global factors, the economy is said to weaken due to sluggish domestic consumption. In the first quarter of 2015, year-on-year growth of private consumption was down to 5.0% compared to 5.4% in Q1 2014.

Figure 3: Real Private Consumption in Indonesia (Q1 2013 – Q1 2015)

Frost & Sullivan believes that scrapping luxury tax is likely to be a suitable method to boost domestic consumption. The policy will be implemented during the month of Ramadan, which has always been a period of consumption spree. On top of that, the policy comes into effect during the Jakarta Great Sale event, which will be an effective avenue to increase sales of luxury products. Aside from implementation period, scrapping luxury tax could be an effective mechanism to boost consumption due to the variety of products in which luxury taxes are lifted. Not only that it applies to branded fashion products, luxury tax is no longer imposed to consumer durables such as television, stove, and refrigerator.

Policy incoherence

This year, the GOI tax revenue target amounts to Rp1,294.3 trillion, a 4.0% increase from the 2014 target. The GOI is experiencing constraints to achieve the target, due to declining tax revenue from various sources such as import tax and oil and gas sector. Actual revenues from VAT on imports declined by 10.0% while tax revenue from the oil and gas sector, Indonesia’s largest economic sector, declines by 53.8% on year-on-year basis in Q1 2015. The revocation of luxury goods tax is not in line with what the GOI is trying to achieve. It may actually further perpetuate the issue on declining tax revenue that GOI is currently experiencing.

Exchange rate pressure

Many products classified as luxury goods, including branded items, are not crafted in Indonesia. Imports of luxury items, especially branded fashion items, always exceed the amount of branded goods exports from Indonesia. For instance, in Q4 2014, imports of perfumes reached US$ 26.0 million, according to BPS. In comparison, perfumes exports for the same period amounted to only US$ 23.9 million. If the GOI cannot effectively enforce the local content policy, imports of luxury items will flourish the Indonesian market. Such situations are likely to further depress an already weak current account balance of Indonesia.

Growing domestic demand for luxury items may induce excessive demand for foreign currency. This will eventually create a downward pressure to Indonesia’s exchange rate. Frost & Sullivan believes that careful attention needs to be paid in implementing the new luxury tax policy. Without an effective measure to boost exports, the tax policy may render the Rupiah to plunge even further.

Implication to Indonesia’s luxury goods market

Driving domestic demand for luxury goods

Scrapping luxury goods tax is likely to boost domestic demand for luxury goods. While the affluent population is an important customer base, Frost & Sullivan believes that middle-class segment will be an additional customer base that is likely to drive the luxury goods market in Indonesia. For many middle-class citizens, luxury items imply prestige. People want to show that they are attached to premium social status by buying branded handbags, state-of-the-art cameras, and other premium items. The revocation of luxury goods tax is likely to reduce the retail price of many luxury goods and making it more affordable for the luxury-craving middle class population.

Furthermore, according to Indonesian Shopping Centre Association (APPBI), the new tax policy is likely to prevent Indonesians from purchasing similar products in other countries. With Indonesia issuing a new visa-free policy, – now includes 45 countries in total – scrapping luxury goods tax may also attract more foreign tourists to shop for luxury items in Indonesia. Overall, these expected results will drive the luxury goods market going forward.

Policy durability

While the new tax policy may be beneficial to boost domestic luxury market, it is imperative for industry participants to highlight the durability of this policy. Criticisms have been launched at the policy. According to one member of the House of Representative, the policy will only result in a large social cost due to possible widening inequality gap. As mentioned, the new tax policy may also have negative long term consequences to the economy, through reduction in realized tax revenue and downward pressure to the Rupiah.

Frost & Sullivan believes that the long term detrimental economic effects and social pressures are likely to make the policy short-lived. The GOI may scrap the policy once the objective to boost domestic consumption is achieved and the economy strengthens. Further, economic policy-making in Indonesia is often replete with nationalistic tone. If the new luxury tax policy propels imports of luxury goods from abroad, Frost & Sullivan opines that it is likely that the nationalist voices will raise concerns and pressure the GOI to revoke the policy.

Conclusion

The revocation of luxury goods tax can be an effective mechanism to boost domestic consumption in Indonesia, amid current economic slowdown. The affluent population will be the major source of demand. But, with luxury goods prices expected to decline, the aspiring middle-class segments will make the attempt to purchase luxury products as a method to climb the social status ladder. Frost & Sullivan believes that with Indonesia’s burgeoning middle-class size, demand for luxury goods will increase and thus, positively contribute to the luxury goods market. Overall, this can boost domestic consumption and propel economic improvements in Indonesia.

Yet, there are some structural issues that may outweigh the ostensible benefits from implementing the new luxury tax policy. Scrapping luxury goods tax may not be coherent with the GOI’s aim to boost tax revenues. Further, the increment in domestic consumption for luxury goods may have to be met with imports which will further depress the currency. Given Indonesia’s embedded nationalism in policy-making, it is likely that the new luxury tax policy will only be a temporary measure to expedite economic improvement. It is imperative for investors and industry participants to pay careful attention to and understand the economic and social impacts of the new luxury tax policy.