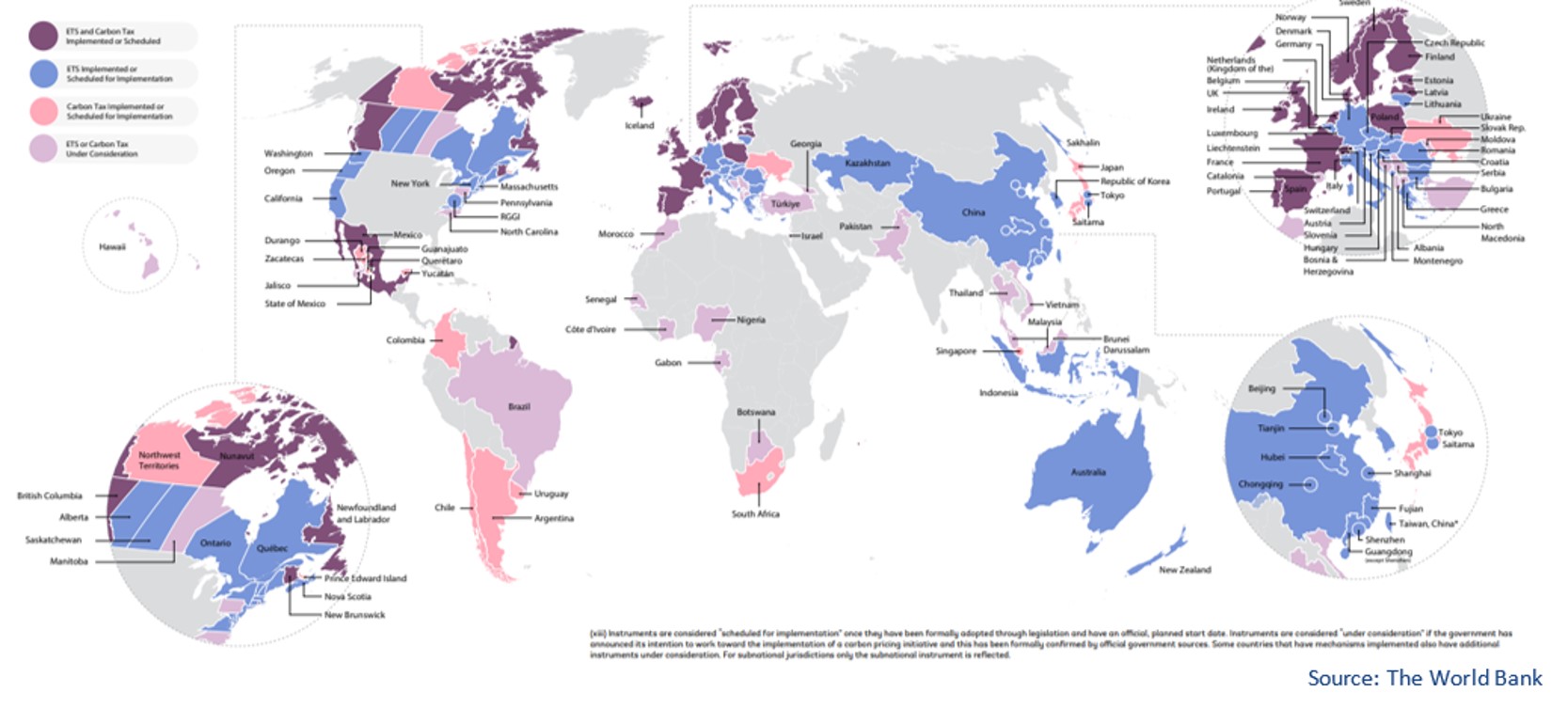

Status of Carbon Market Taxes and ETSs across Regions: Under Consideration, Scheduled for Implementation or Implemented/scheduled

Carbon taxes penalize businesses for emitting carbon dioxide (CO2), thus fostering a reduction of emissions, whereas carbon markets or ETSs enable the exchange of carbon credits or carbon offsets to compensate for excess emissions, launching a dynamic and complex market that brings together businesses that manage these offsets through different methodologies and verify their functioning.

Verification standards have been implemented to ensure prices are adequate and processes are correct, guaranteeing the legitimacy of offsetting practices. Moreover, the proliferation of systems and initiatives has demonstrated the need for cooperation and coordination, which has prompted the establishment of several partnerships and associations that cultivate knowledge and expertise exchanges. Not only are governments enforcing these targets through legally binding systems, but consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the environmental impact of their actions, pressing companies to incorporate sustainable practices to maximize profit and sales. The rapid evolution of these markets has driven the development of platforms to respond to consumers’ demands and access new market segments, allowing individuals, as well as companies, to contribute to the achievement of global targets. A mature digital economy focused on sustainability facilitates the transition of policies to platforms, integrating governments, the private sector, and civil society.

The 6P Framework for the Future of the Sustainability and Circular Economy – More with Less

Policies: The Beginning of Carbon Markets

In 2015, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) brought the international community together and laid out a series of objectives to be achieved by 2030. For instance, this agenda promotes the sustainable use of resources and renewable energies, smart cities, and the preservation of ecosystems and biodiversity. The goals are not independent of each other but rather contribute to a general underlying idea of sustainable growth, which allows for carbon offsetting projects to not only tackle the limited objective of climate action but also provide further benefits such as the conservation of marine life or the use of renewable energies, which translates into added value – both revenue and sustainability-wise.

In line with Goal 13 of limiting and adapting to climate change, the Paris Agreement encourages the international trading of emission allowances. Multilateral cooperation on the matter has fostered the implementation of ETSs on an international, national, and subnational level, strengthening the commitment towards carbon targets and prompting a proliferation of organizations and platforms that boost these efforts. This agreement builds on and corrects the failed mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol, that were ineffective in reducing emissions. As of 2016, the Paris Agreement has established two new market mechanisms: Article 6.2, which enables countries to sell credits (known as Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes) for any extra reduction that they have achieved beyond their target; and Article 6.4, which authorizes the implementation of diverse projects to reduce and offset carbon emissions, sold in the form of credits to any country, company, or person. The former can yield an excessive reliance on credits without carrying out any substantial climate action domestically and can result in a lack of quality control over the credits sold. The latter mechanism inevitably implies the existence of some verification entity, which has brought about a series of auditing businesses and standards that influence the prices of credits, since these standards testify to the project’s legitimacy.

Products: The Commercialization of Carbon Credits and Offsets

Carbon markets are on the rise. Societal awareness and governmental legislation are fundamental drivers for said growth, since they compel companies to operate within sustainable standards, ensuring their compliance with both legal and market requirements. Emissions Trading Systems, also known as carbon markets, are based on the commercialization of carbon credits.

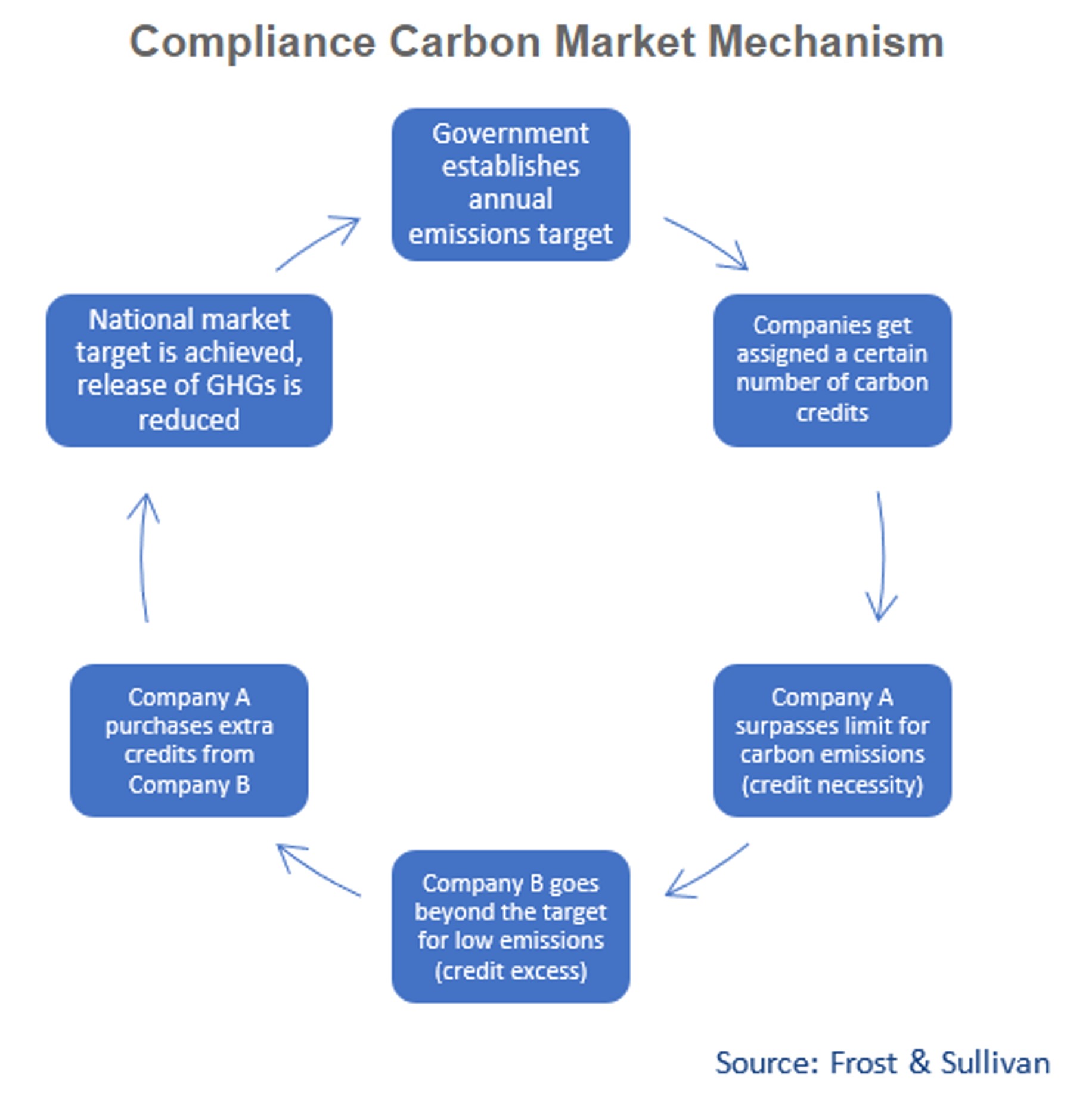

Companies that diligently seek or are obliged to offset their emissions can purchase these credits from other entities that actively sell them or have remaining credits they will not be using. The key distinction is the legal requirement to offset emissions, which differentiates both segments of the carbon market: while the compliance market is constructed around Cap-and-Trade Agreements established by government policies, the voluntary market consists of the proactive purchase of carbon credits to reduce a company’s carbon footprint.

A carbon credit represents a ton of CO2 released into the global atmosphere. Within a Cap-and-Trade System, these emission allowances are allocated to companies by governments, combined with a target for the reduction of GHGs emissions. Accordingly, each company gets a certain number of credits that they can use annually to ensure the emissions target (the “cap”) is achieved.

Nevertheless, credits can and must be exchanged (for a price) between companies, instituting a carbon market or ETS, where organizations with a surplus carbon balance can sell their remaining carbon credits to others who are set to emit excess gases. These exchanges are mandatory to achieve a legal target, but they can also be great sources of revenue, pressuring companies to reduce their emissions for the sake of being able to sell excess credits and avoid acquiring more.

Nevertheless, credits can and must be exchanged (for a price) between companies, instituting a carbon market or ETS, where organizations with a surplus carbon balance can sell their remaining carbon credits to others who are set to emit excess gases. These exchanges are mandatory to achieve a legal target, but they can also be great sources of revenue, pressuring companies to reduce their emissions for the sake of being able to sell excess credits and avoid acquiring more.

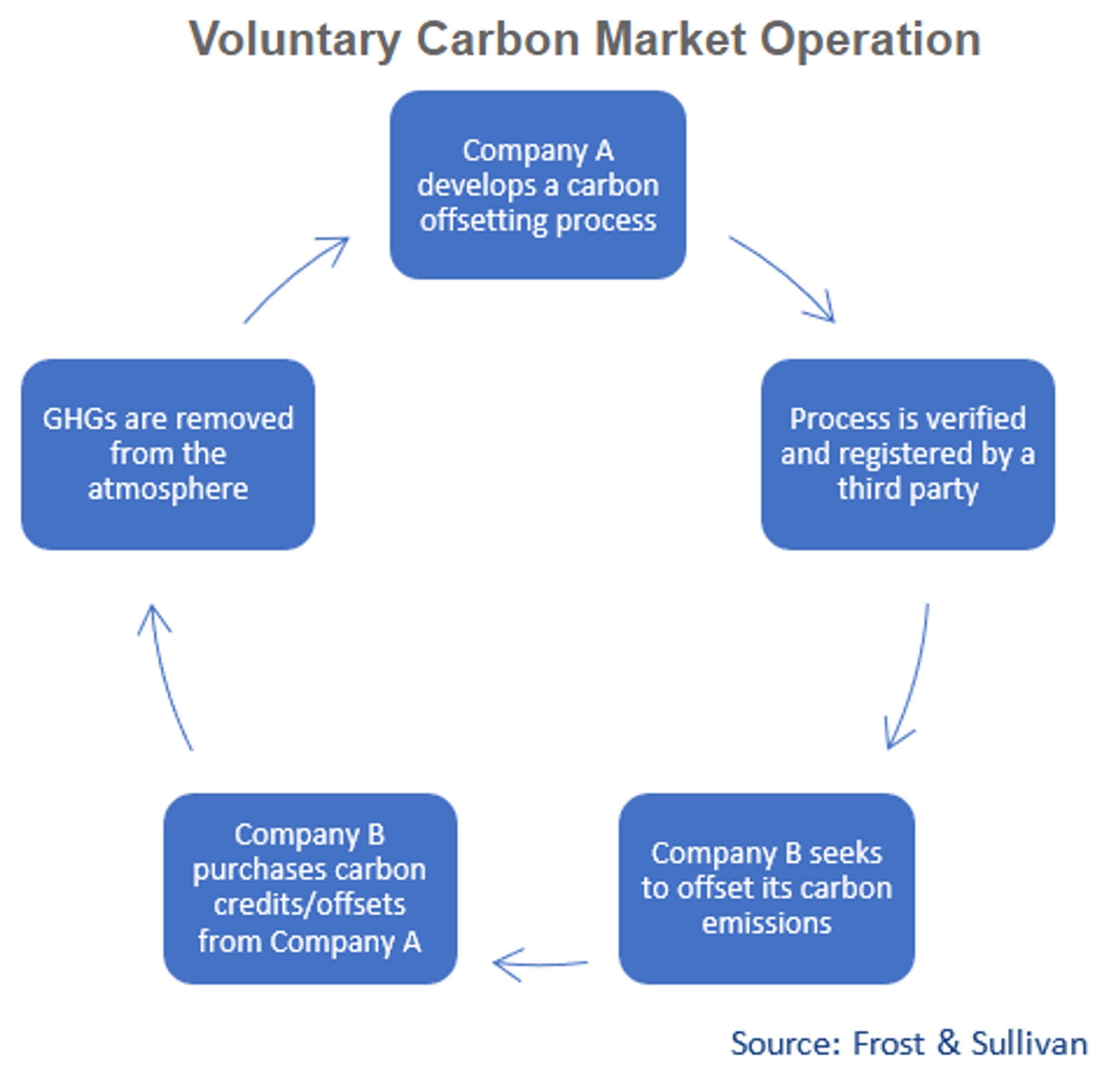

Conversely, a carbon offset consists of the removal of GHGs from the atmosphere to compensate for a certain number of emissions. These can be purchased independently of an emissions target by companies who wish to go beyond said target or are not subject to any. Government policies do not drive these exchanges, the purchase of these offsets by any individual or organization is purely voluntary (which is not to say it cannot be influenced by a marketing or revenue-seeking purpose), articulated around an underlying market approach to sustainable practices.

Conversely, a carbon offset consists of the removal of GHGs from the atmosphere to compensate for a certain number of emissions. These can be purchased independently of an emissions target by companies who wish to go beyond said target or are not subject to any. Government policies do not drive these exchanges, the purchase of these offsets by any individual or organization is purely voluntary (which is not to say it cannot be influenced by a marketing or revenue-seeking purpose), articulated around an underlying market approach to sustainable practices.

The European Energy Exchange Group (EEX) classifies credits commercialized in the voluntary carbon market in a similar way but with different terminology. The EEX refers to credits as Reduction/Avoidance Credits or Removal Credits, as well as categorizing them based on the type of solution, whether they are nature- or technology-based.

An essential challenge in both market segments is the double counting of carbon reductions. Exchanges between countries create the risk of both entities registering the reduction towards the achievement of their target, hence doubling the global number. Similarly, when a company contributes to the national offsetting target, it should refrain from considering those numbers as “extra” capture because they are already listed as national contributions.

Processes: Nature-Based Solutions for Carbon Offsetting

Given that increasing commercialization of carbon credits is expected to drive investment in carbon offsetting processes, the establishment of criteria to determine if a practice can be considered sustainable is crucial. Green taxonomies provide these rules for investment and help avoid issues of verification and greenwashing, ensuring the authentic offsetting processes credits are built on. The underlying guideline of protecting and restoring natural resources, ecosystems, and communities is at the core of the implementation of nature-based solutions (NbS) for climate change. These aim to preserve land and biodiversity, hence preventing GHGs emissions, as well as capturing and storing carbon via carbon farming and reforestation, among other practices. Nature-based solutions are compatible and not a replacement for engineered or technology-based solutions, but they do present a cost advantage that can make them especially attractive for developing economies, where soil degradation is usually prevalent due to the focus on agriculture and livestock farming. Moreover, they have added benefits such as improving climate resilience and prevention of natural disasters.

For instance, Shell is implementing a multi-dimensional approach to achieving their net-zero target by reducing their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, while they invest in technology and nature-based carbon capture. The company claims to “buy carbon credits generated by projects that protect nature and restore the environment.”

People: Integrated View of Carbon Markets

The creation of carbon markets has cultivated joint efforts from governments and the private sector to reduce emissions, bringing forth a set of leading industry players both revenue and policy-wise.

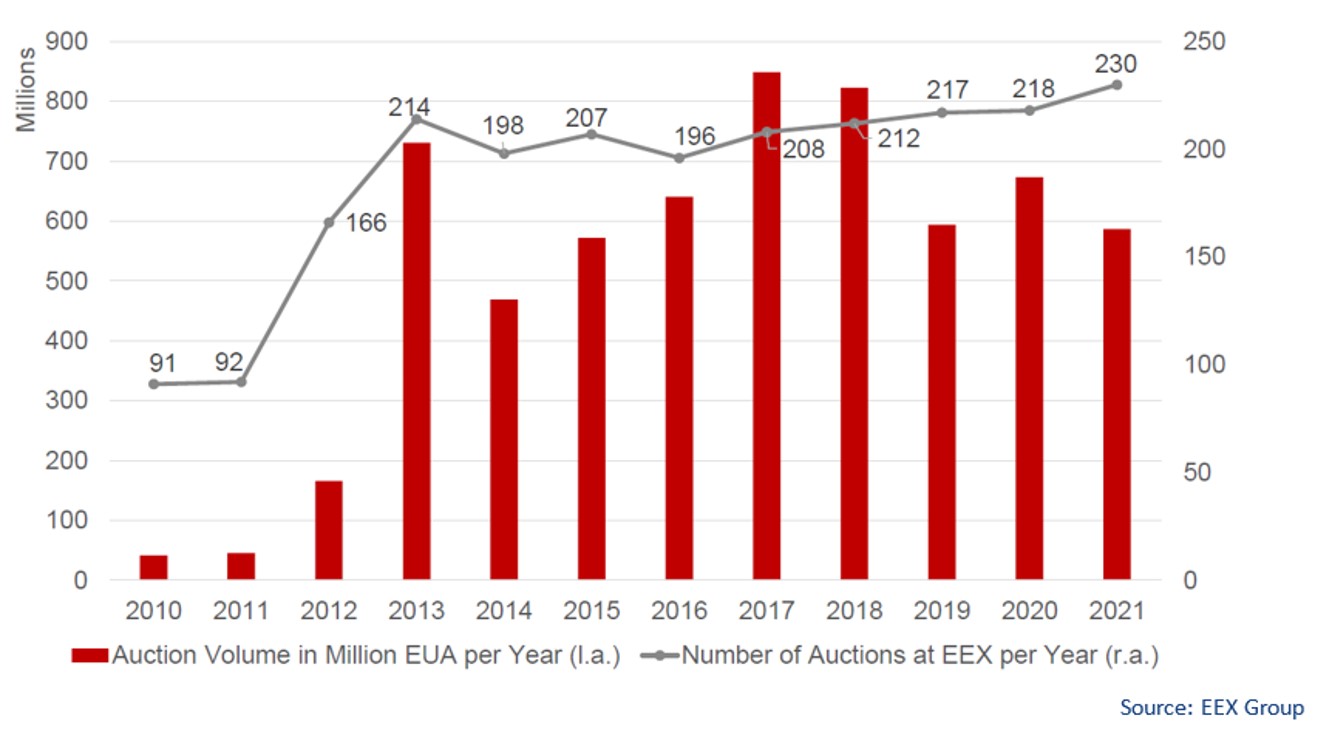

Firstly, the European Union (EU) is the leading governmental institution in the carbon industry. The EU has forged a pioneering system with ambitious and exceptional targets, encompassing key industries such as aviation, power, and energy-intensive activities, with upcoming incorporations of new customer segments: the domestic maritime sector in 2026 and waste in 2028. The EU’s commitment to sustainable growth triggered the implementation of the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, which focuses on activities that protect biodiversity and resources, such as nature-based solutions. The European trading system has the widest emissions coverage and highest revenue in the world, combined with an underlying green strategy toward sustainable growth. The emissions allowances are mainly traded through auctioning via the European Energy Exchange Group (EEX), which also participates in the voluntary carbon market. The EU states that have a surplus of allowances auction these in the EEX platform, the EU common auction platform, trading both European Union Allowances (EUAs) and EU Aviation Allowances (EUAAs). The following graphic showcases the evolution of the number of auctions of EUA held at EEX in the last decade and the auction volume, which is determined annually.

Evolution of EEX Auctions for the EU ETS: 2010-2021

Other state actors such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and Korea are progressively adjusting their targets and strengthening their pledges.

Regarding businesses, a BloombergNEF report indicates that most carbon offset buyers are business-to-consumer (B2C) companies, such as Delta Air Lines, Shell, Volkswagen, and Audi. These companies are integrating carbon offset purchasing into their corporate sustainability strategies. Conversely, leading companies selling offsets include 8 Billion Trees, TerraPass, and Native Energy Solutions.

A company worth mentioning is Tesla. By incorporating sustainable practices into its production activities, Tesla has managed to attain a surplus balance that has positioned it as a dominant credit seller under California’s Cap-and-Trade Program. According to the company’s financial reports, credit-selling accounts for 3% of its total revenue, with Fiat Chrysler as its largest carbon customer in the past few years.

Partnerships: Knowledge and Expertise Exchange

Successful examples of ETSs, such as the European ETS, provide guidelines and best practices that can foster and facilitate the development of this type of initiative in other countries. Both the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) and the Partnership for Market Implementation (PMI) offer platforms for knowledge exchange, promoting the consolidation and linkage of carbon markets. Robust national strategies can better the prospects for international coordination and achievement of carbon targets, which explains the relevancy and wide support for these partnerships. Other forums such as the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) focus on market solutions and standards from a business rather than a country perspective but are nevertheless fundamental players in the carbon market.

Additionally, there are several partnerships aimed at the development of nature-based solutions, such as The NBS Coalition and the Enhancing Nature-based Solutions for an Accelerated Climate Transformation (ENACT), which foster collaboration for the implementation of NbS, integrating not only governments but other non-state actors. Likewise, The NDC Partnership strives to provide support and resources to countries that require assistance carrying out climate actions to achieve the targets set by both the Paris Agreement and the SDGs.

Platforms: The Digital Economy Driving Growth

The digital economy unleashes the full potential of carbon trading by boosting sales and democratizing access. Several platforms allow individuals to buy credits and manage their portfolios, such as Xpansiv or EEX, which operate in both the compliance and voluntary markets and account for a dominant portion of the market size in both segments. Xpansiv is a major market player, trading ESG-inclusive commodities (carbon, renewable energy, water, and natural gas) from around 400 market participants. Likewise, Pachama offers a wide range of forest projects to both businesses and individuals who wish to offset their carbon emissions. The company has partnered with brands such as Salesforce and Workday, and its user-friendly layout enables easy access to certified projects. There are many other available platforms, such as the Carbon Trade Exchange, one of the earliest players in the market that only operates in the voluntary segment, or Nori, among others.

Market Overview: Drivers of continuous growth

Both voluntary and compliance markets are set to grow in the coming decades. The compliance market is still the biggest segment, comprised of 36 ETSs and 37 carbon taxes mechanisms around the world. The global revenue for the year 2022 was US$100 billion, a US$16 billion increase from the previous year (according to the World Bank’s Carbon Pricing Dashboard and State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2022 and 2023 reports). Not only are government policies and climate targets expected to become increasingly rigorous but there are also several potential systems under consideration, implying the market is not fully mature. Most of its revenue can be attributed to the EU ETS, which accounts for around 90% of the market size, followed by smaller initiatives such as the Western Climate Initiative and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (both in North America). The EU’s net-zero target by 2050 can signify a short and medium-term increase in revenue that would value the market at well over US$200 billion by 2030 if the growth rate is stable, which is likely to be outperformed. A stabilizing growth rate (at least in the EU ETS) may characterize the long-term as net-zero emissions are approached and there are fewer credits to be commercialized, which can cultivate potential growth opportunities for other newer and less developed systems.

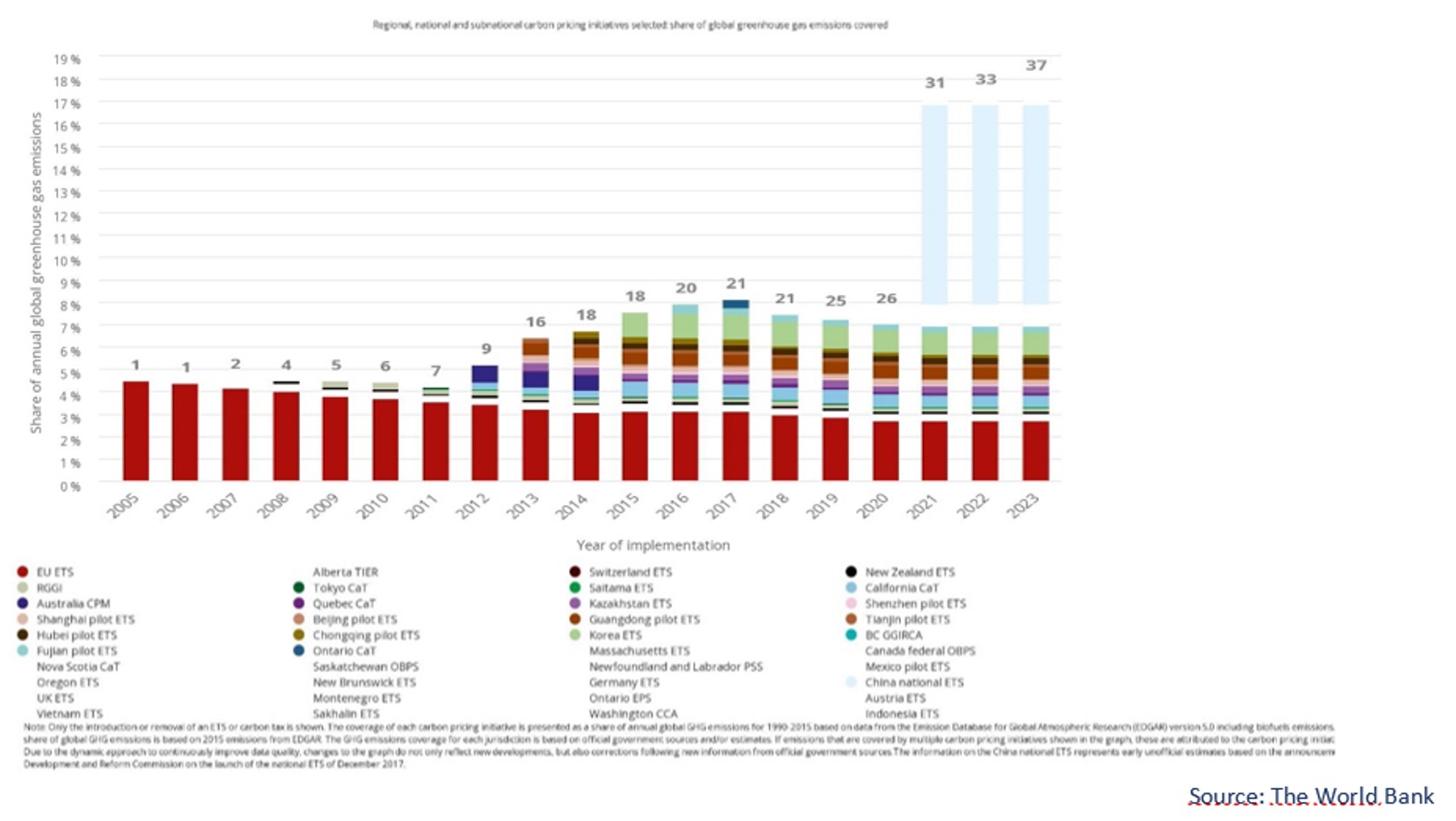

The World Bank has set up a Carbon Pricing Dashboard where different mechanisms are analyzed on both revenue and emissions coverage. Price and revenue-wise, the most successful systems are the European Union’s and the UK ETS. The following graphic shows the coverage evolution of GHGs emissions under ETSs or compliance markets. As new countries and regions are incorporating Cap-and-Trade Agreements into their policies, the number of emissions covered is set to increase. It is important to note that the EU ETS has the widest coverage, but as previously mentioned, the European Union’s commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 implies their contribution will continuously decrease. In the last decade, the number of instruments has doubled, but the coverage has not expanded accordingly, which may be attributed to looser targets and commitments.

Share of GHGs Emissions Covered by Emissions Trading Systems

On the other hand, according to a report published by Ecosystem Marketplace, the voluntary carbon market size was estimated at over US$2 billion in 2022, having quadrupled since 2020. Due to its outstanding growth prospects in both the short and long-term, the voluntary market is estimated to be worth at least US$10 billion by the year 2030, considering a stable and similar growth as the last few years. Given rising awareness of the environmental impact of carbon emissions, individuals and companies are set to intensify their investments to reduce their carbon footprint, thus combining a soaring demand with a price drop caused by technological advancements and industry development, which is why this growth rate is likely to be surpassed. In addition, the general market depression that took place between 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic could indicate that the growth rate underperformed, and the full market potential was not reached. It is relevant to consider that prices are also dependent on standard validation and the expected authenticity of each purchased carbon offset, which can be controlled and verified by third-party auditors. For instance, the Gold Standard Foundation manages one of the most renowned carbon offsetting standards, based on a set of rules a carbon credit needs to follow to be verified and registered.

The NbS industry needs to improve and develop to maximize revenue and efficiency, given that capturing one ton of CO2 currently requires approximately 50 trees growing for a whole year. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, US$154 billion is being invested in the nature-based solutions industry per year, with reforestation and land use projects representing over half of the total market revenue, followed by renewable energies. There are considerable investment opportunities for the private sector in this thriving industry, even if most of the current contributions are government-originated.

Companies that adapt to the carbon industry can expect considerable revenue growth, whether by selling carbon credits under an ETS or by incorporating carbon offsetting into their daily activities and sales, tackling both government policies and consumers’ needs. For instance, some companies allow buyers to add carbon offsets to their purchase for a small price, such as Galaxus, which has calculated emissions for their products based on both production and delivery.

Going Beyond Offsetting Towards Net-Zero Emissions

Trading systems can be helpful in balancing global emissions and aiding countries that are struggling with reduction mechanisms on their own, but they are not the ultimate solution. It is critical to strengthen targets and pledges towards net-zero emissions through both domestic and international climate action, striving to avoid and not only compensate for emissions. Issues such as greenwashing and double counting will become especially relevant as countries and companies perceive the increasing societal pressure for sustainable practices. Individuals have gained access to the voluntary markets to offset their own carbon footprint, but it is vital to combine this commitment with a powerful campaign for the institution of ambitious but viable net-zero policies that can tackle the root cause of climate change, lowering the caps on ETSs rapidly.

Upcoming Frost & Sullivan’s growth opportunity analysis dedicated to Climate Solutions: Climate Tech Top 50, focusing on solutions for climate adaptation and mitigation, including water technologies, AgTech, and circular economy, among others.